The temporary’s key findings are:

- About half of older adults will find yourself requiring some high-intensity long-term care (LTC).

- The evaluation explores whether or not individuals precisely understand their LTC dangers, evaluating subjective and goal survey questions.

- It seems that the subjective measures will not be good proxies for goal threat.

- However the variation within the subjective responses means that Blacks, Hispanics, and ladies could also be underestimating their dangers.

- These three teams additionally are inclined to have fewer assets to cowl care wants.

Introduction

Many older adults would require some long-term care (LTC) later in life, with over half needing intensive assist – typically for an prolonged interval. The assets required to fulfill such high-intensity, long-duration wants – both casual assist from members of the family or paid formal care – could be substantial. The query is whether or not older adults perceive their dangers and whether or not the accuracy of their perceptions varies by socioeconomic traits.

Regardless of the massive literature on LTC dangers and insurance coverage, little or no analysis has targeted on whether or not individuals have sense of how a lot assist they could want with every day actions as they age. Those that overestimate their threat may maintain on to their nest egg and unnecessarily limit their consumption in retirement, whereas those that underestimate their threat may expertise unmet wants or need to spend right down to qualify for Medicaid. This temporary, based mostly on a current paper, compares two measures of self-assessed LTC dangers with goal possibilities of ending up with high-intensity care wants.1

The dialogue proceeds as follows. The primary part offers some background on LTC dangers general, how care is offered, and the restricted analysis on self-assessed LTC dangers. The second part defines how we measure goal and subjective dangers. The third part assesses whether or not the out there measures of subjective dangers seize the identical idea as the target dangers. The ultimate part concludes that neither of the subjective measures are good proxies for goal threat. However analyzing how the subjective responses differ by demographics does present some helpful insights. Particularly, Blacks and Hispanics seem optimistic about their future wants relative to different teams. And whereas girls appear to concentrate on common LTC dangers, they could not notice that they face higher-than-average dangers of needing care. These findings are regarding as these teams not solely have the very best goal dangers of needing high-intensity care, in addition they have fewer assets to supply for this care.

Background

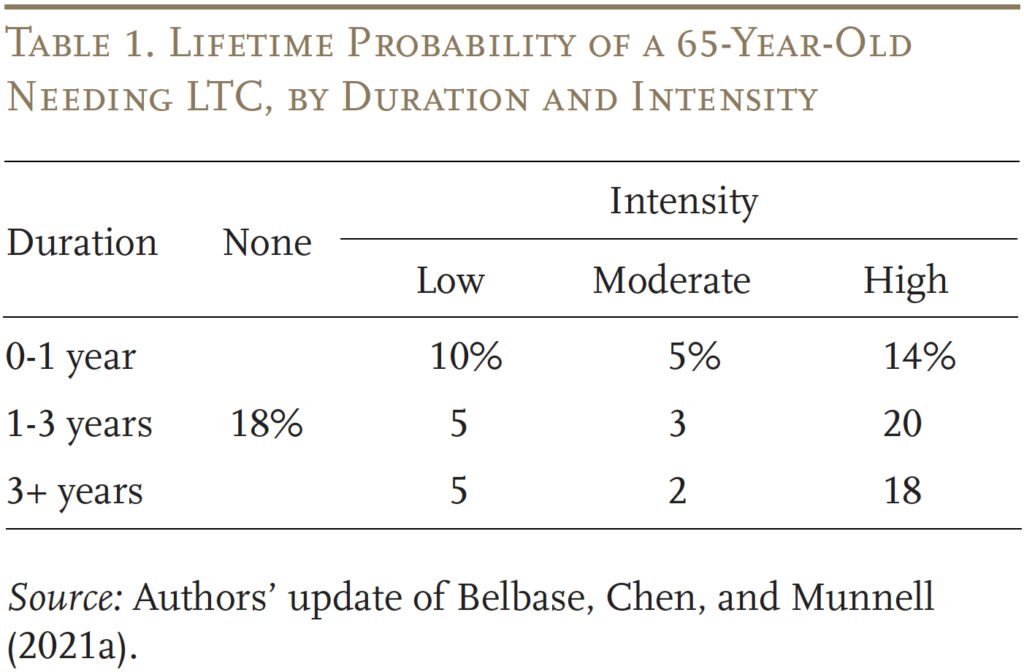

As individuals age, most finally need assistance with housekeeping or different instrumental actions of every day residing (IADLs) like procuring or getting ready meals, and typically with extra important duties, or actions of every day residing (ADLs) like bathing, consuming, and toileting. Whereas some can get by with help a couple of occasions per week (low depth), over half of older adults can have high-intensity wants – that’s, require assist with two or extra ADLs or have an Alzheimer’s/dementia prognosis – typically for an prolonged interval (see Desk 1).2

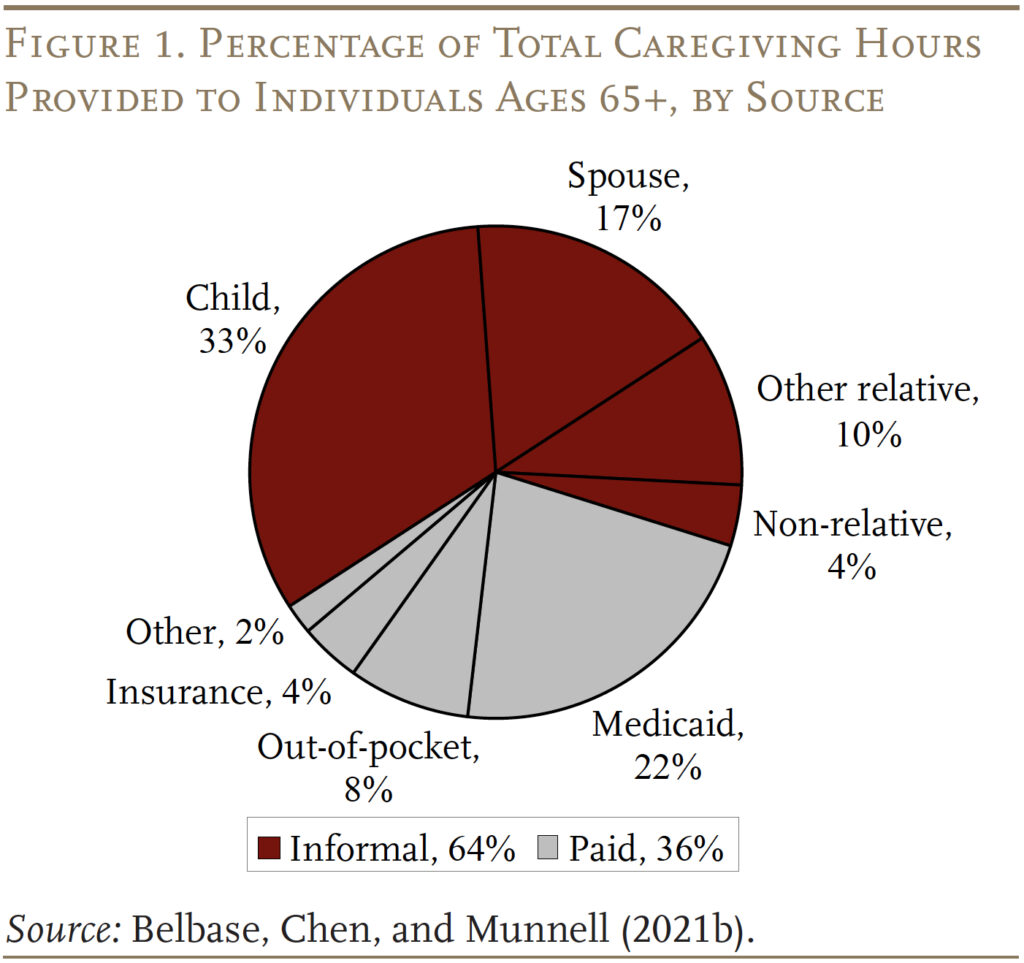

Households cowl these long-term care wants in two methods. The extra frequent method is unpaid casual care offered by members of the family (see Determine 1). The much less frequent method is paid formal care, financed primarily via Medicaid or out-of-pocket. At present, lower than 5 % of adults have long-term care insurance coverage, and qualifying for Medicaid requires households to impoverish themselves.3

The assets required to fulfill high-intensity LTC wants, both from members of the family or paid formal care, could be substantial. To plan successfully, older adults want a sensible evaluation of their dangers. Sadly, the extent to which older adults have understanding of their very own LTC dangers is essentially unknown.4

One of many few related research examines the probability of people ages 72+ needing nursing dwelling care within the subsequent 5 years.5 The outcomes present that, in mixture, respondents have a fairly good sense of their future nursing dwelling wants. Nonetheless, respondents who say they may doubtless want a nursing dwelling within the subsequent 5 years are more likely to be unwell already. It isn’t clear whether or not youthful, more healthy retirees or near-retirees have comparable predictions about their future LTC wants.

The evaluation beneath appears at two measures of self-assessed LTC wants and whether or not these measures can provide helpful comparisons to predicted goal possibilities of getting such wants.

Measuring Goal and Subjective Dangers

The information for the evaluation come from the Well being and Retirement Examine (HRS), a nationally consultant biennial longitudinal survey of U.S. adults ages 51 and older and their companions.

Goal Dangers of Excessive-Depth Care

The target measure focuses on older people’ threat of needing 90+ days of high-intensity care.6 For roughly 60 % of the pattern, it’s doable to watch the whole lifespan of the person and their LTC wants; for the opposite 40 %, who’re nonetheless alive, their lifetime wants are projected based mostly on the expertise of present and older cohorts from earlier surveys.7 Lifetime dangers are based mostly on the person’s most extreme expertise. That’s, an individual who wants assist cleansing and cooking in her 60s, then has a bout of most cancers in her 70s that requires some assist a couple of occasions per week, after which develops dementia in her 80s that requires around-the-clock care could be counted as soon as and categorized as having high-intensity LTC wants.

Subjective Dangers of Excessive-Depth Care

Older adults’ self-assessed threat of needing high-intensity care comes from two HRS questions: 1) “What’s the % probability that you’ll ever have to maneuver to a nursing dwelling?” and a couple of) “Assuming that you’re nonetheless residing at age 85, what are the possibilities that you’ll be free of significant issues in pondering, reasoning, or remembering issues that will intervene together with your skill to handle your personal affairs?”8 For each questions, members reply with a quantity between 0 and 100, the place 0 means they see no probability that the occasion will occur and 100 means they assume the occasion will happen with certainty. Within the case of the cognition query, the inverse of the response represents the respondent’s perceived dangers of getting severe cognitive limitations.9

Neither query is a perfect measure of the necessity for high-intensity LTC. For the primary query, persons are more likely to fee their prospects of transferring to a nursing dwelling decrease than their perceived LTC wants, each as a result of nursing houses are unpopular and since individuals can more and more get some high-intensity care in their very own houses.10 For the second query, the wording is broad sufficient to cowl milder types of cognitive decline (e.g., typically forgetting to pay payments), which makes it more likely to generate “greater” measures of perceived threat in comparison with a metric targeted solely on dementia prognosis.11 However these two questions are the one ones out there within the HRS to function proxies for anticipated LTC.

Outcomes

This part begins with the outcomes for goal dangers after which compares them to respondents’ self-assessed dangers.

Goal Dangers

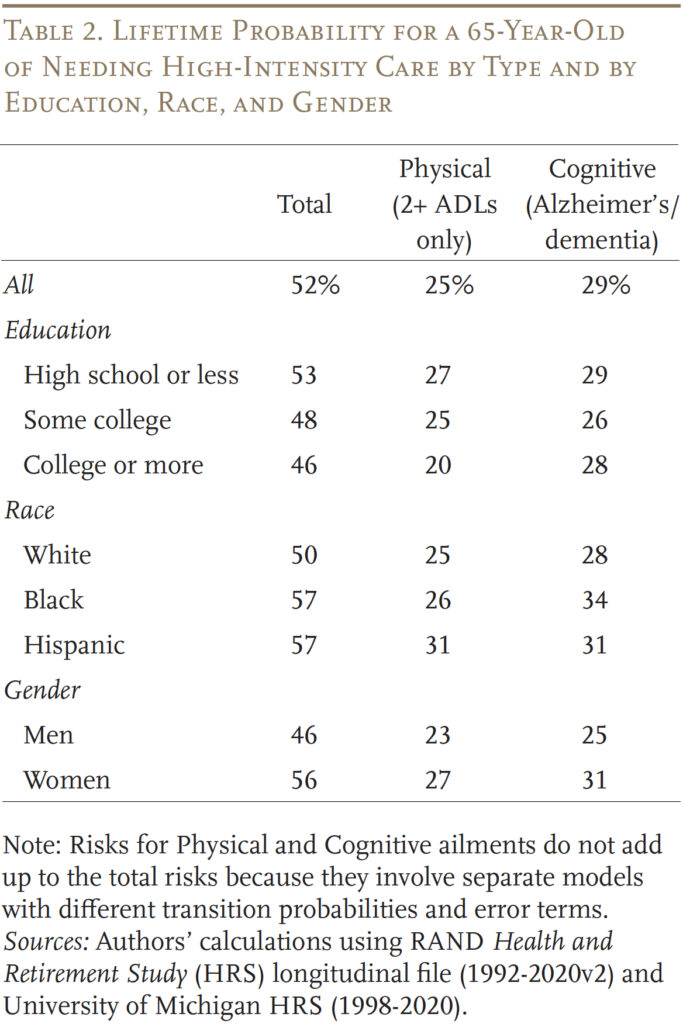

The outcomes present that 52 % of these 65+ will want high-intensity take care of greater than 90 days sooner or later over their remaining lifetime (see Desk 2). Roughly half of these wants are generated by bodily illnesses and half from cognitive decline. The proportion in danger varies by schooling, race, and gender. Particularly, these with much less schooling, Blacks and Hispanics, and ladies have a higher-than-average probability of needing high-intensity LTC.

Evaluating Goal and Subjective Dangers

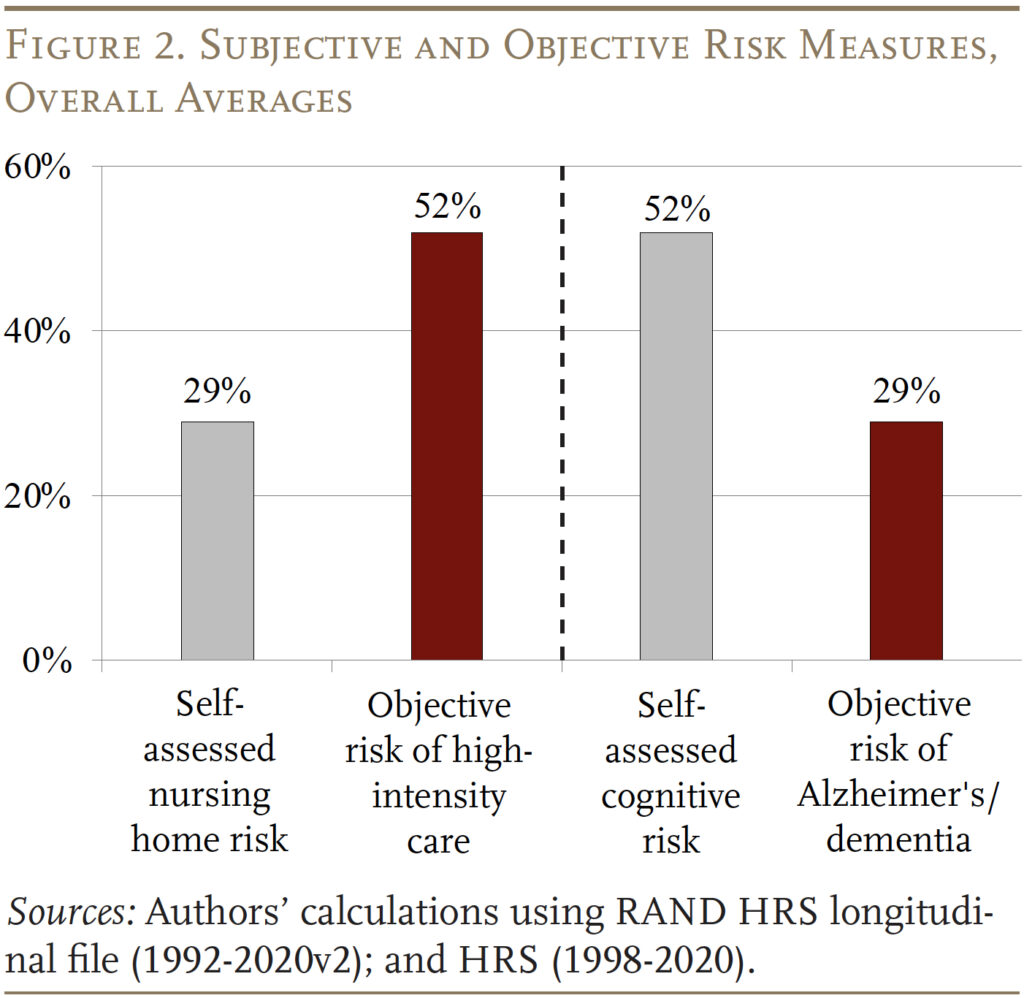

Determine 2 compares: 1) HRS respondents’ subjective threat of ever ending up in a nursing dwelling with the target threat of needing any high-intensity care; and a couple of) respondents’ subjective threat of needing assist with cognitive decline with the target prognosis of Alzheimer’s illness or different dementia. Sadly, these outcomes match our expectations. Self-assessed nursing dwelling threat – at 29 % – is considerably decrease than the target measure of high-intensity LTC wants, as individuals typically dislike the thought of getting into a nursing dwelling and residential care could also be a viable different. And self-assessed cognitive threat – at 52 % – is way greater than the target threat of Alzheimer’s/dementia as a result of the HRS cognitive query is so broad.

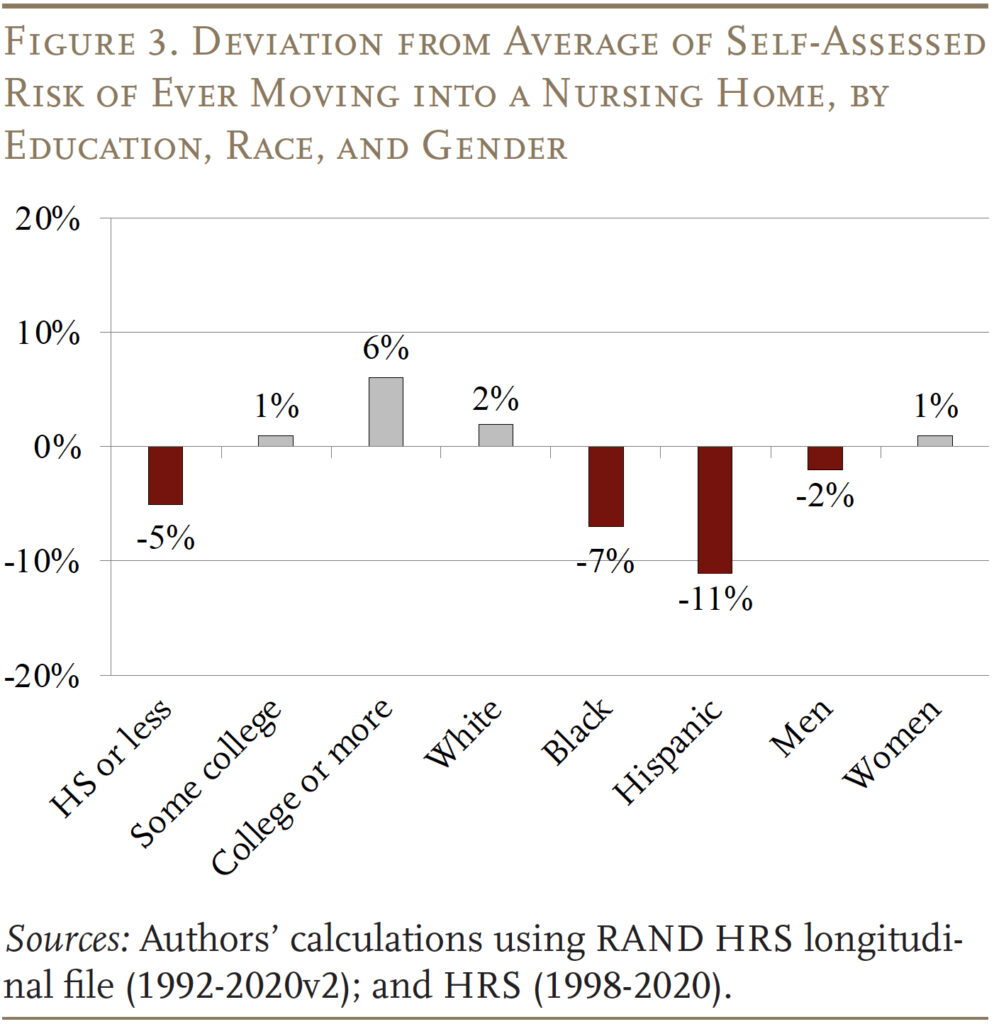

Whereas the HRS questions are doubtless not good measures of older households’ perceived high-intensity future wants, the variation in responses by demographics offers some helpful insights. By way of ever transferring right into a nursing dwelling, Blacks, Hispanics, and people with a highschool diploma or much less understand their dangers to be considerably beneath common (see Determine 3). As famous earlier, these teams face the next probability of needing high-intensity LTC.

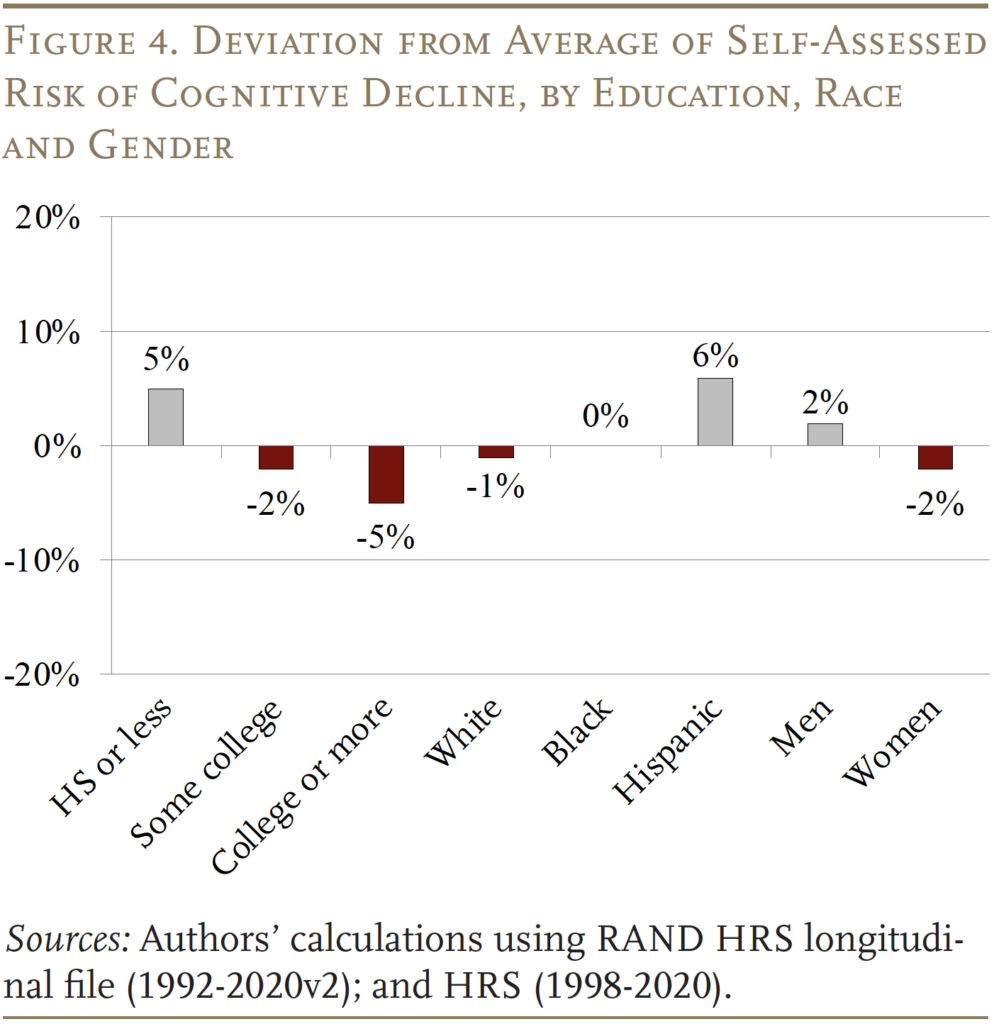

By way of cognitive decline, assessments are typically extra uniform throughout teams, however girls and people with a minimum of some faculty are extra sanguine about needing assist than others (see Determine 4). Girls are barely extra optimistic even though they’ve a higher-than-average threat.

Conclusion

This temporary examined two measures of self-assessed LTC dangers together with goal possibilities of ending up with high-intensity care wants. The outcomes point out that neither of the self-assessed measures are good proxies for capturing self-assessed high-intensity wants. Nonetheless, trying on the demographic breakdowns for the self-assessments does present some helpful insights. Particularly, Blacks and Hispanics could also be underestimating their dangers of future LTC wants. And whereas girls appear to concentrate on common LTC dangers, they could not notice that they face higher-than-average dangers of needing care. In brief, the teams which have the next likelihood of high-intensity wants as they age even have fewer assets to supply for his or her care.

You will need to be aware that even being conscious of LTC dangers doesn’t equate to being financially ready to deal with the prices of offering excessive ranges of care. However, a primary step in being ready is knowing the extent to which these dangers exist. Future analysis may design questions that higher seize older adults’ perceived LTC dangers.

References

Related Press-NORC Heart for Public Affairs Analysis. 2015. “Lengthy-Time period Care in America: Individuals’ Outlook and Planning for Future Care.” Chicago, IL.

Related Press-NORC Heart for Public Affairs Analysis. 2021. “Lengthy-Time period Care in America: Individuals Wish to Age at Dwelling.” Chicago, IL.

Belbase, Anek, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2021a. “What Stage of Lengthy-Time period Providers and Helps Do Retirees Want?” Challenge in Transient 21-10. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston Faculty.

Belbase, Anek, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2021b. “What Sources to Retirees Have for Lengthy-Time period Providers & Helps?” Challenge in Transient 21-16. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston Faculty.

Brown, Jeffrey R., Gopi Shah Goda, and Kathleen McGarry. 2012. “Lengthy-term Care Insurance coverage Demand Restricted by Beliefs about Wants, Considerations about Insurers, and Care Accessible from Household.” Well being Affairs 31(6): 1294-1302.

Chen, Anqi, Alicia H. Munnell, and Nilufer Gok. 2025. “Do Households Have a Good Sense of Their Lengthy-Time period Care Dangers?” Working Paper 2025-1. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston Faculty.

Finkelstein, Amy and Kathleen McGarry. 2006. “A number of Dimensions of Non-public Info: Proof from the Lengthy-term Care Insurance coverage Market.” American Financial Assessment 96(4): 938-958.

Henning-Smith, Carrie E. and Tetyana P. Shippee. 2015. “Expectations About Future Use of Lengthy-Time period Providers and Helps Range by Present Dwelling Association.” Well being Affairs 34(1): 39-47.

Hinton, Ladson, Duyen Tran, Kate Peak, Oanh L. Meyer, and Ana R. Quiñones. 2024. “Mapping Racial and Ethnic Healthcare Disparities for Individuals Dwelling with Dementia: A Scoping Assessment.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 20 (4): 3000-3020.

Johnson, Richard. 2019. “What Is the Lifetime Danger of Needing and Receiving Lengthy-Time period Providers and Helps?” Analysis Transient. Washington, DC: U.S. Division of Well being and Human Providers.

Khatutsky, Galina, Joshua M. Wiener, Angela M. Greene, and Nga T. Thach. 2017. “Expertise, Information, and Considerations about Lengthy-Time period Providers and Helps: Implications for Financing Reform.” Journal of Growing older & Social Coverage 29(1): 51-69.

LIMRA. 2022. “Do Customers Actually Perceive Lengthy-Time period Care Insurance coverage?” Information Launch (November 15). Windsor, CT.

Lin, Pei-Jung, Allan T. Daly, Natalia Olchanski, Joshua T. Cohen, Peter J. Neumann, Jessica D. Faul, Howard M. Fillit, and Karen M. Freund. 2022. “Dementia Analysis Disparities by Race and Ethnicity.” Medical Care 59(8): 679-686.

Pauly, Mark V. 1990. “The Rational Nonpurchase of Lengthy-Time period-Care Insurance coverage.” Journal of Political Economic system 98(1): 132-168.

RAND. Well being and Retirement Examine Longitudinal File, 1992-2020v2. Santa Monica, CA.

Robison, Julie, Noreen Shugrue, Richard H. Fortinsky, and Cynthia Gruman. 2013. “Lengthy-Time period Helps and Providers Planning for the Future: Implications from a Statewide Survey of Child Boomers and Older Adults.” Edited by John B. Williamson. The Gerontologist 54(2): 297-313.

Spillman, Brenda C., Jennifer Wolff, Vicki A. Freedman, and Judith D. Jasper. 2014. “Casual Caregiving for Older Individuals: An Evaluation of the 2011 Nationwide Examine of Caregiving.” Washington, DC: U.S. Division of Well being and Human Providers, Workplace of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Analysis.

Swaddiwudhipong, Nol, David J. Whiteside, Frank H. Hezemans, Duncan Avenue, James B. Rowe, and Timothy Rittman. 2023. “Pre-diagnostic Cognitive and Useful Impairment in A number of Sporadic Neurodegenerative Ailments.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 19(5): 1752-1763.

College of Michigan. Well being and Retirement Examine, 1992-2020. Ann Arbor, MI.