The transient’s key findings are:

- One purpose for the persistence of the racial wealth hole may very well be that Black households are far much less doubtless than their White counterparts to have a will.

- Having a will results in bigger bequests, and those that obtain an inheritance usually tend to have extra wealth and go away their very own bequest.

- The evaluation explored how a lot equalizing will-writing charges between Black and White households might slender the wealth hole.

- The outcomes present that eliminating the will-writing hole would have narrowed the wealth hole by – a modest however significant – 10 % over three generations.

Introduction

The hole in wealth between Black and White households has plagued the US for greater than a century. One purpose for the shortage of progress could also be a disparity in will-writing by race – Black households are far much less more likely to have a legitimate will than their White counterparts. Having a will is related to leaving bigger bequests, and those that obtain extra in inheritances are additionally extra more likely to go away a legacy themselves. Thus, adopting a will would doubtless improve the wealth of all future generations and scale back the racial wealth hole.

To estimate the attainable impression of wills, this transient, which relies on a latest research, explores how a lot equalizing will-writing charges between Black and White households would have narrowed the wealth hole over the previous few generations.1 A complicating issue is that not all of the correlation between will-writing and bequests is causal: many people write wills as a result of they want to go away a bequest reasonably than the opposite manner round. To account for this probability, the evaluation makes use of two approaches, another reduced-form and another structural. We refer to those approaches as “top-down” and “bottom-up.” Whereas neither strategy is ideal, collectively they supply helpful higher and decrease bounds for the impression of will-writing on wealth.

The dialogue proceeds as follows. The primary part presents background on the racial wealth hole, the racial “will hole,” and the speculation behind why wills may improve family wealth throughout generations. The second part particulars the 2 analytical approaches used to estimate how eliminating the will-writing hole might have an effect on the wealth hole. The third part describes the outcomes. The ultimate part concludes that eliminating the racial hole in will-writing might slender the wealth hole by a modest however significant 10 % over three generations.

Background

This part describes the essential info on the racial wealth hole and its evolution, and summarizes the present literature on the racial “will hole.”

The Racial Wealth Hole: Previous and Current

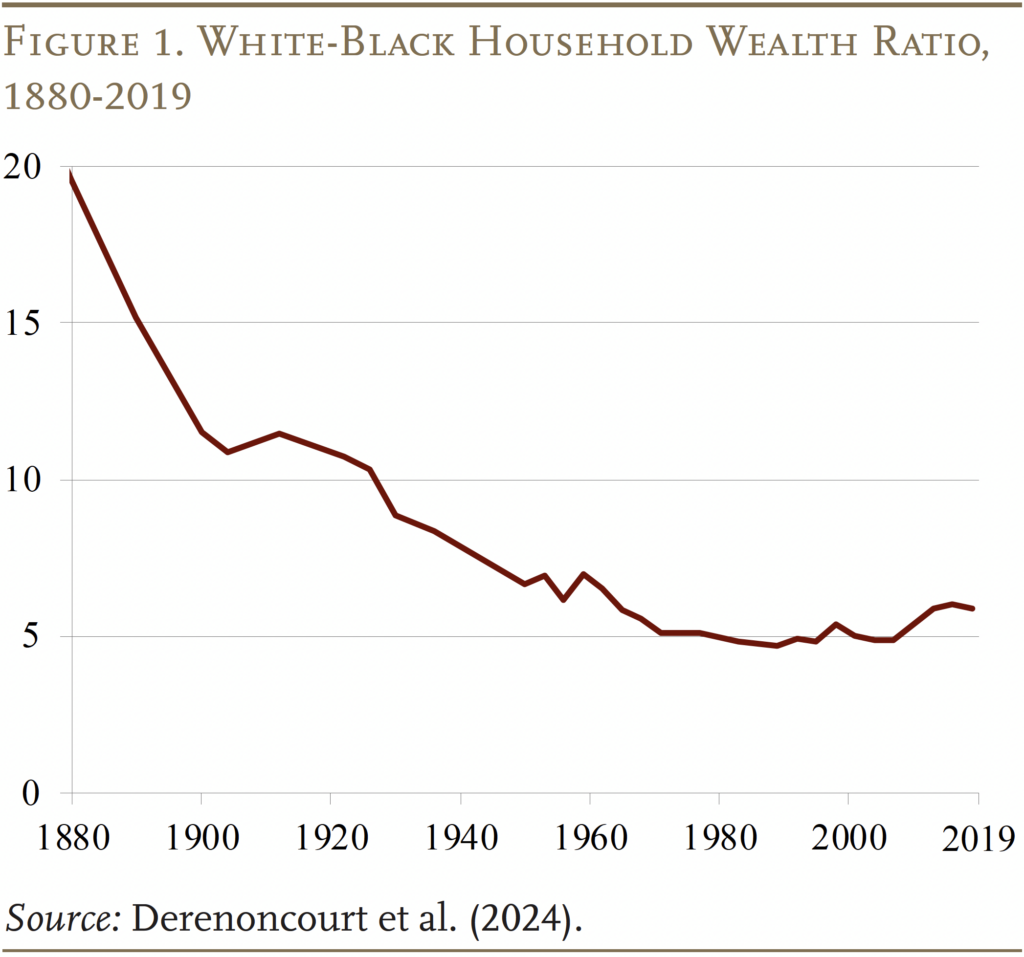

Between 1880 and 1950, the ratio of White-to-Black family wealth declined dramatically. Nevertheless, since then, progress has stalled. In 2019, the racial wealth hole remained at 6-to-1, with proof that it has been rising wider because the Nineteen Eighties (see Determine 1).2

The present racial wealth hole is way bigger than one would count on if White and Black households had loved equal charges of saving and equal returns on their belongings. On this case, the method of convergence would have resulted in a 3-to-1 hole in 2020.3 The truth that the present ratio is twice this benchmark is generally on account of decrease saving charges for Black households. Nevertheless, in the previous few many years, racial variations in asset returns have grow to be more and more vital – a sample that has pushed the latest widening of the racial wealth hole.

Researchers have explored why Black buyers earn decrease returns than their White counterparts. Partially, the distinction is because of completely different portfolios. Black households have a tendency to carry a bigger share of their wealth in housing than monetary belongings – notably equities – and housing yields decrease returns than equities over the long term.4 To some extent, nonetheless, the racial distinction in returns additionally displays decrease returns on the identical kind of asset. For instance, house-value appreciation is decrease for Black owners, a consequence of variations in location and foreclosures charges.5

The principle exercise explored on this transient – will-writing – straddles the 2 explanations for the sluggish convergence in wealth between Black and White households. That’s, each decrease saving charges and decrease returns are related to the racial hole in will-writing. On the racial distinction in saving charges, the proof means that people with a will intend to depart bigger bequests and likewise usually tend to meet these expectations, suggesting they’re placing apart extra sources for future generations.6 Moreover, those that obtain an inheritance usually tend to go away a bequest themselves, compounding these generational beneficial properties and growing the racial wealth hole.7

As well as, some portion of the racial distinction in returns can also be associated to the hole in wills.8 Authorized consultants routinely argue that dying intestate is a specific drawback when the property is modest and the most important asset is the home, the place a number of heirs are sometimes unable to coordinate on sustaining or promoting the property, destroying worth within the course of.9 Alternatively, if the meant beneficiaries reside within the decedent’s house, the distribution to a lot of beneficiaries might consequence within the pressured sale of the property. Therefore, a racial distinction within the dissipation of belongings when bequeathed, pushed by a racial hole in wills, is a attainable contributor to the racial wealth hole that has not obtained a lot consideration so far.

The Black-White Will Hole

Given the potential impression of will-writing on financial savings, leaving bequests, and sustaining the worth of transferred belongings, the Black-White hole in will-writing helps clarify why the racial wealth hole has elevated in latest many years. Certainly, Black people obtain fewer and smaller inheritances than White ones, and are additionally much less more likely to intend to depart a bequest or to have a legitimate will.10

Particularly, Black households are 20 share factors much less more likely to have a legitimate will than their White counterparts, even after adjusting for traits equivalent to wealth, training, presence of residing kids, and having obtained an inheritance prior to now.11 Equally, Black respondents additionally report considerably decrease possibilities of leaving substantial bequests to their heirs. Furthermore, when analyzing the realized estates of decedents, those that had a will have been considerably extra more likely to attain their bequest expectations.

The present research builds on these findings, and asks whether or not closing the racial will hole might contribute to closing the racial wealth hole. Particularly, we ask how a lot the racial wealth hole would have shrunk during the last three generations if Black households had the identical will-writing charges as Whites.

Information and Methodology

Answering this query includes evaluating two wealth estimates for consultant White and Black households: one during which the Black and White will-writing charges are held at their present ranges, and one during which the Black price is elevated to that of White households. The evaluation begins with an preliminary White-Black wealth hole estimated as of 1980 for households with a head ages 60-70 – an age span when households are having fun with their peak lifetime wealth. All of the evaluation relies on knowledge from the Well being and Retirement Research (HRS), a longitudinal panel survey of a consultant pattern of households ages 50 and older.12 The evaluation then tracks the wealth of consultant White and Black households over three 20-year generations – 2000, 2020, and 2040.

For this evaluation, the estimates of wealth throughout generations rely crucially on two relationships: 1) obtained inheritances and late-life wealth; and a pair of) late-life wealth and bequests. Given the potential sensitivity of the outcomes to those relationships, the evaluation makes use of two complementary approaches: a diminished kind “top-down” strategy, which estimates each relationships instantly; and a structural “bottom-up” strategy, which estimates the impression of inheritances on wealth not directly, by making use of assumed returns to a obtained inheritance.

The High-Down Strategy

The highest-down strategy permits the info to instantly inform how obtained inheritances translate into later-life wealth and, by way of the wealth-bequest relationship, into eventual transfers to the following era. That’s,

Late-life wealth = f (inheritances and management variables)

the place late-life wealth is family wealth at ages 60-70, inheritances are the overall obtained over the lifetime of the family, and controls embrace details about the pinnacle’s gender, race, marital standing, kids, and retirement standing.

Bequests are then a perform of the family’s late-life wealth (housing and non-housing), outlined profit (DB) wealth (which is handled individually as a result of it’s not bequeathable), and the identical management variables as above.

Bequests = f (late-life wealth, DB wealth, has a will, and management variables)

The benefit of the top-down strategy is that the myriad of ways in which an inheritance could be utilized are left open to recipients. For instance, they might use the cash to fund investments in bodily or human capital (equivalent to healthcare or training); they might use it as a buffer for the pursuit of a riskier however extra rewarding occupation; or they might use it to finance consumption.

The drawback of this strategy is omitted variable bias. That’s, if excessive socioeconomic standing recipients usually tend to obtain inheritances and be rich in later life, the top-down strategy could overestimate the effectiveness of bequests in growing the wealth of subsequent generations. For instance, if the kids of upper-class households usually tend to be excessive earners, or to marry into different rich households, their eventual wealth shouldn’t be attributed solely to the inheritance they obtain.

The Backside-Up Strategy

To keep away from this drawback, the bottom-up strategy focuses in the marketplace mechanisms by way of which an inheritance may improve later-life wealth. That’s, inheritances are both consumed or invested. To the extent they’re invested, they earn market returns. This strategy excludes every other elements that could be correlated with receiving an inheritance, equivalent to marrying properly. It requires analyzing housing wealth and monetary wealth individually as a result of they earn completely different returns and play a unique function in bequests. The related equation for each housing and non-housing wealth is:

Housing bequest / Non-housing bequest = f (housing wealth, non-housing wealth, DB wealth, has a will, and management variables)

Estimating the Change in Wealth throughout Generations

With the coefficients from these regressions in hand, the bequest from every era to its subsequent era could be estimated by plugging within the imply values of all controls, and taking account of late-life wealth by race and the related will-writing price. This course of yields the expected bequest left by every era, which is then divided by the typical variety of kids to acquire an estimated inheritance per baby (3.3 kids for the Black households and a pair of.8 for the White ones). This amount then turns into an enter to a second estimation: predicting the late-life wealth of the successor era given the inheritances they obtain.

The method is barely extra difficult for the bottom-up strategy, as a result of it requires a variety of assumptions. First, the marginal propensity to devour out of inheritances is assumed to be 0.06 for housing wealth and 0.15 for non-housing wealth.13 The common age at which households obtain an inheritance is assumed to be 58.14 After consumption, the mannequin tasks 22 years of progress for housing and non-housing wealth, bringing households to age 80 – roughly the life expectancy at age 58.15 Robustness checks included within the full paper present that the ultimate outcomes are comparatively insensitive to the return and holding-period assumptions.

Collectively, the top-down and bottom-up approaches yield outcomes that may certain the impression of will-writing on the racial wealth hole.

Outcomes

This part begins with the outcomes of the top-down evaluation, adopted by these from the bottom-up strategy.

High-Down Outcomes

To provide the top-down outcomes, step one is to estimate the wealth/inheritance and bequest/wealth relationships described within the first two equations on the earlier web page. This reduced-form strategy reveals that an extra greenback of inheritance obtained all through life is related to $3 of further wealth at ages 60-70. So, inheritances do matter.

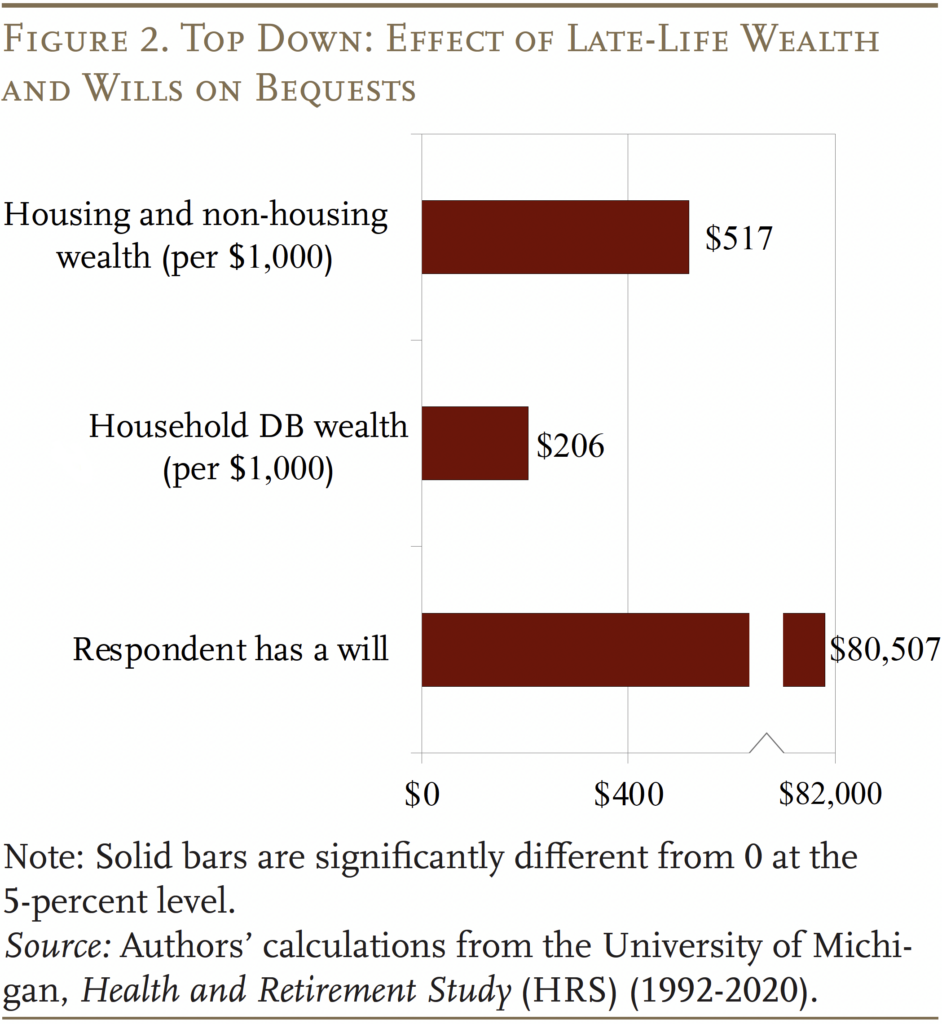

By way of bequests, Determine 2 reveals that an extra $1,000 in bequeathable belongings round ages 60-70 is related to $517 extra left in bequests. An extra $1,000 in current worth of DB wealth, in the meantime, interprets into $206 of further bequest (presumably by way of lowering reliance on different belongings throughout retirement). All else equal, having a will is related to a rise within the common bequest of $80,507. So, wills do matter.

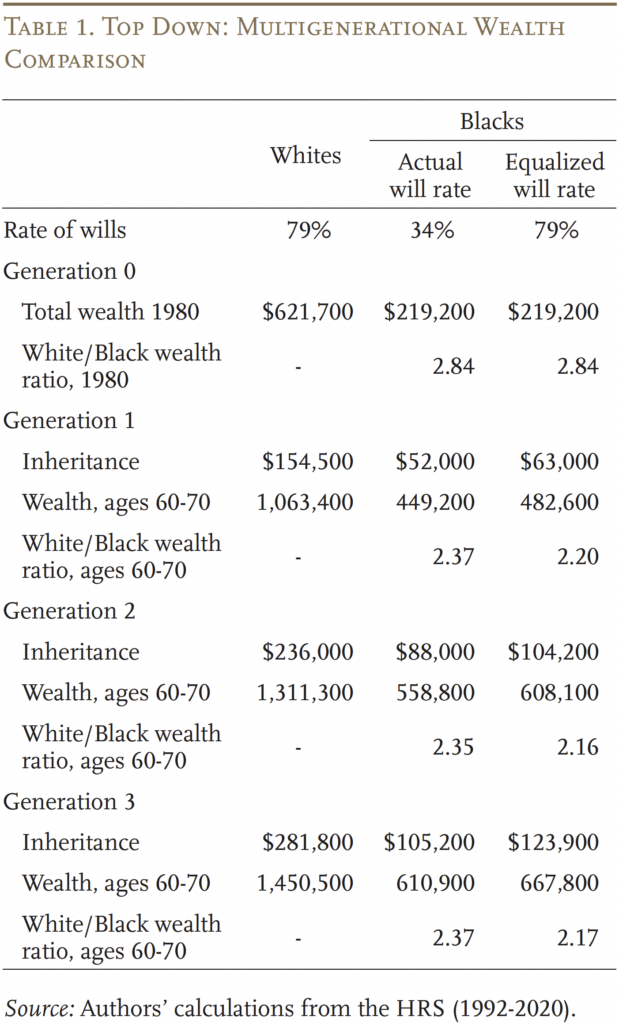

Given these estimates, Desk 1 reveals the outcomes of the top-down evaluation. The evaluation begins in Technology 0, the place 79 % of White family heads have a will in contrast with 34 % of Black households. In 1980, White wealth was $621,700, whereas Black wealth was solely $219,200 (all in 2020 {dollars}), resulting in a White-Black wealth ratio of two.84. (This ratio differs from the numbers in Determine 1 on account of variations in knowledge sources and within the wealth measure used.)

From this start line, the primary era receives an inheritance of $154,500 for White beneficiaries and $52,000 for Black ones, beneath the precise will-writing price. The estimated relationship between inheritances obtained and late-life wealth then interprets into $1,063,400 in late-life wealth for White households, and $449,200 for Black ones, yielding a White-Black wealth ratio of two.37. Alternatively, beneath the belief that Black and White people have the identical will-writing price of 79 %, the ensuing White-Black wealth ratio is just 2.20.

Iterating over the following two generations yields a closing White-Black wealth ratio of two.37 (beneath precise will-writing charges) and a pair of.17 (beneath equal will-writing charges) by the third era. In different phrases, if will-writing charges had been equal beginning in 1980, the racial wealth hole would have declined by practically 10 % over three generations.

Backside-Up Outcomes

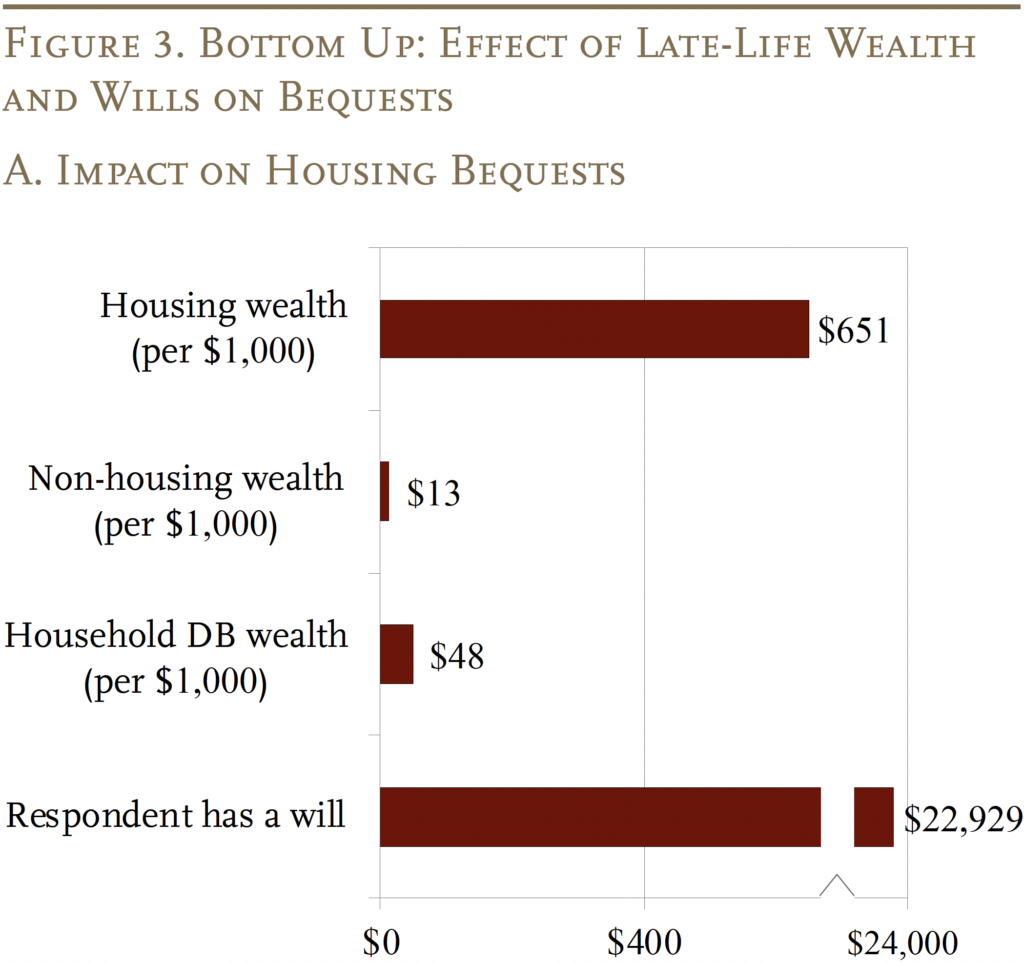

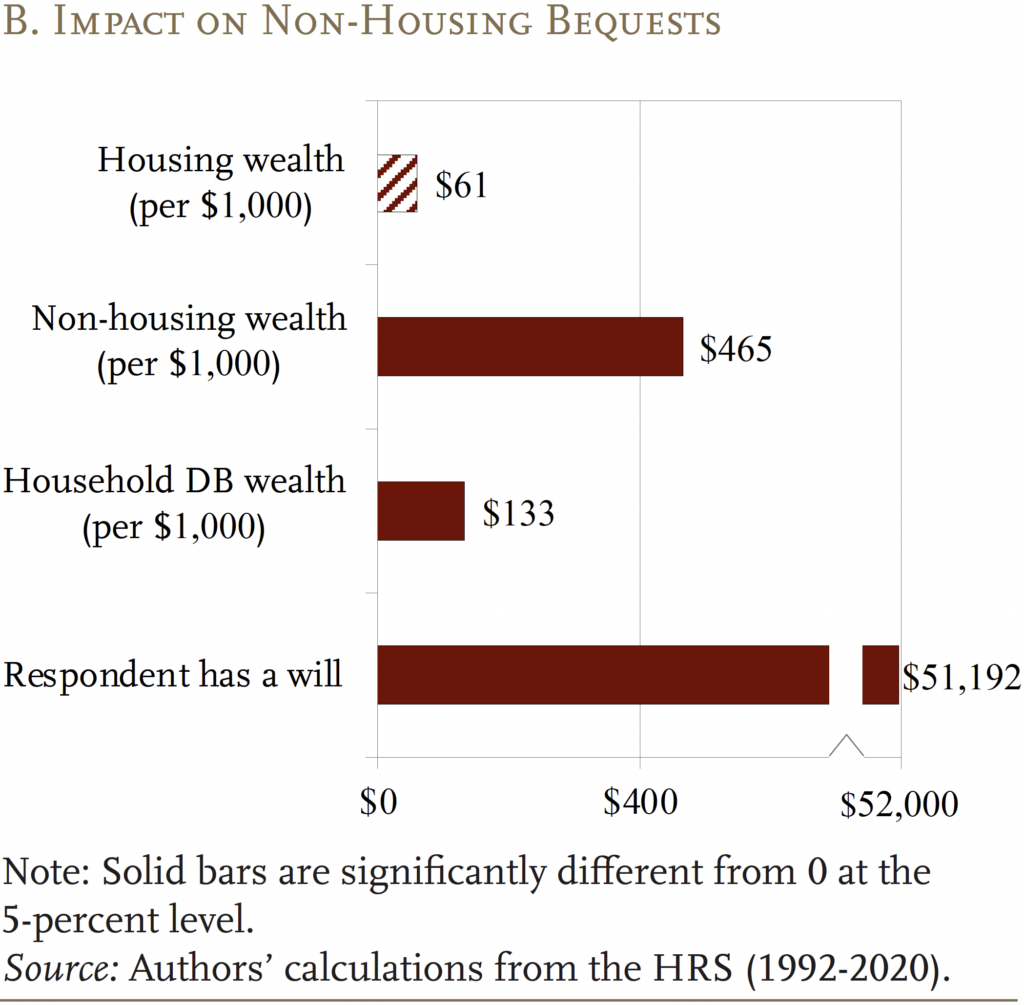

As mentioned, the bottom-up strategy requires estimating housing and non-housing wealth individually (see Determine 3). Unsurprisingly, the worth of housing wealth is strongly related to housing bequests, whereas non-housing wealth is equally strongly related to eventual non-housing bequests. Particularly, each $1,000 of housing wealth is related to an extra $651 of housing bequests, whereas each $1,000 of non-housing wealth is related to an extra $465 of non-housing bequests. The quantity of DB wealth has solely a modest affiliation with each housing and non-housing bequests.16

As with the top-down strategy, the outcomes present that, holding all else equal, having a will is strongly associated to the worth of the decedent’s property, each when it comes to housing and non-housing wealth. A decedent with a will leaves, on common, $22,929 extra housing wealth and $51,192 extra non-housing wealth.

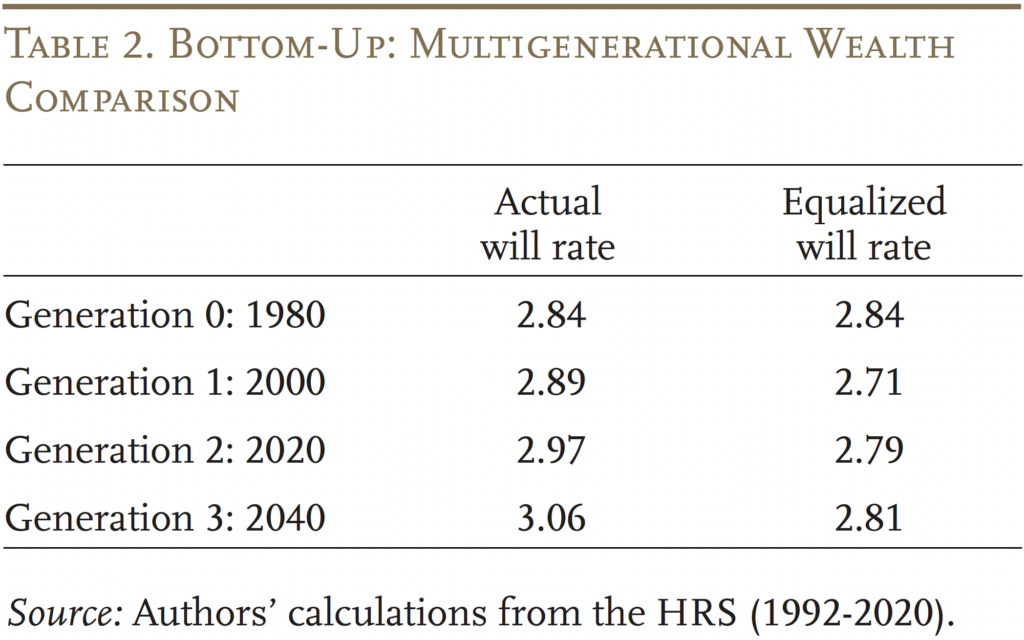

With these estimates in hand, Desk 2 summarizes the impression of bringing the will-writing price for Black households as much as that of their White counterparts. (The entire step-by-step train is offered within the full paper.) Technology 0 is equivalent to the beginning era within the top-down strategy, however the bottom-up strategy anticipates higher racial wealth inequality. By way of how equalizing will-writing in 1980 would have affected the racial wealth hole, once more the outcomes present that this modification would have had a significant impression. By the third era, the mannequin predicts that the White-Black wealth ratio can be 3.06 with precise will-writing charges, and solely 2.81 with racially equal charges. That’s, equalizing will-writing in 1980 would have diminished the ratio by about 10 %.

This 10-percent estimate is remarkably just like the top-down strategy, regardless of a considerably completely different mannequin. The similarity within the outcomes throughout the 2 approaches demonstrates the robustness of the outcomes. This robustness conjures up confidence that growing will-writing amongst Black households might present a modest however significant contribution to narrowing racial wealth gaps.

Conclusion

The racial wealth hole has confirmed to be a persistent drawback, and one purpose could also be that Black decedents have a a lot decrease probability of getting a will. This transient explores how the racial wealth hole may need developed since 1980 had will-writing charges been equal for Black and White households. The strong discovering is that such a change would have modestly however meaningfully diminished the wealth hole – by about 10 % – by the point in the present day’s prime-age staff attain their peak wealth years (ages 60-70) in 2040. Whereas nobody change is more likely to fully shut the racial wealth hole, interventions that improve the will-writing of Black households are one promising avenue for coverage exploration.

References

Angrisani, Marco, Michael Hurd, and Susann Rohwedder. 2019. “The Impact of Housing Wealth Losses on Spending within the Nice Recession.” Financial Inquiry 57(2): 972-996.

Aubry, Jean-Pierre, Alicia H. Munnell, and Gal Wettstein. 2023. “Wills, Wealth, and Race.” Working Paper 2023-10. Chestnut Hill, MA: Middle for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Aubry, Jean-Pierre, Alicia H. Munnell, Gal Wettstein, and Oliver Shih. 2024. “How A lot May Will-Writing Cut back the Racial Wealth Hole?” Working Paper 2024-16. Chestnut Hill, MA: Middle for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Choi, Shinae L., Ian M. McDonough, Minjung Kim, and Giyeom Kim. 2019. “Property Planning Amongst Older Individuals: The Moderating Position of Race and Ethnicity.” Monetary Planning Overview 2(3-4): e1058.

Derenoncourt, Ellora, Chi Hyun Kim, Moritz Kuhn, and Moritz Schularick. 2024. “Wealth of Two Nations: The U.S. Racial Wealth Hole, 1860-2020.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 139(2): 693-750.

Diamond, Rebecca and William F. Diamond. 2024. “Racial Variations within the Whole Fee of Return on Proprietor-Occupied Housing.” Working Paper 32916. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Jordà, Óscar, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. 2019. “The Fee of Return on Every part, 1870-2015.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(3): 1225-1298.

Kaplan, Greg and Giovanni L. Violante. 2022. “The Marginal Propensity to Client in Heterogeneous Agent Fashions.” Working Paper 30013. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Kermani, Amir and Francis Wong. 2021. “Racial Disparities in Housing Returns.” Working Paper 29306. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Kuhn, Moritz, Moritz Schularick, and Ulrike I. Steins. 2020. “Revenue and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949-2016.” Journal of Political Financial system 128(9): 3469-3519.

Liu, Siyan and Laura D. Quinby. 2023. “What Drives the Racial Housing Wealth Hole for Older Owners?” Working Paper 2023-3. Chestnut Hill, MA: Middle for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Munnell, Alicia H. and Annika Sundén (eds). 2003. Loss of life and {Dollars}. Washington, DC: The Brookings Establishment.

Munnell, Alicia H., Geoffrey M.B. Tootell, Lynn E. Browne, and James McEneaney. 1996. “Mortgage Lending in Boston: Deciphering HMDA Information.” The American Financial Overview 86(1): 25-53.

Sabelhaus, John and Jeffrey P. Thompson. 2022. “Racial Wealth Disparities: Reconsidering the Roles of Human Capital and Inheritance.” Working Paper 22-3. Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Financial institution of Boston.

Strand, Palma Pleasure. 2010. “Inheriting Inequality: Wealth, Race and the Legal guidelines of Succession.” Oregon Legislation Overview 89: 453-504.

College of Michigan. Well being and Retirement Research, 1992-2020. Ann Arbor, MI.

U.S. Social Safety Administration. 2024. “Retirement & Survivors Advantages: Life Expectancy Calculator.” Washington, DC.

Wright, Danaya C. 2020. “The Demographics of Intergenerational Transmission of Wealth: An Empirical Research of Testacy and Intestacy on Household Property.” College of Missouri-Kansas Metropolis Legislation Overview 88(3): 665-710.